Withhold your judgment, please

I don't like feedback. I've never liked feedback. Not liking feedback has been problematic as people take it to mean that I don't want to learn and grow. This mindset is so prevalent that I began to believe it myself. What's wrong with me, I wondered, that I can't hear critical feedback? Am I so arrogant as to believe I have nothing to learn from others? Intuitively, I know this isn't true, and yet I balk every time someone offers me feedback. I've come to realize that my desire to learn through listening and reflection is misaligned with the primary technique we have to drive that learning. Feedback fails us.

In 2009 I wrote a post entitled The Inadequacy of Feedback. It focused specifically on the feedback forms that are handed out by trainers and presenters after... well, just about everything these days! In that post I asked if there are better ways of giving feedback. More recently I've realised this is the wrong question. A more interesting question would be, how can we learn without feedback?

Feedback from another human being is judgment. Not sometimes, but always. Whether the feedback is complimentary or critical it is a judgment made by the giver on the receiver. I don't care for your judgments, so your feedback has no meaning to me. It is just a nuisance. It sucks me into a conversation with you, or worse, with myself, that I don't want to have and from which I learn nothing.

Positive feedback, compliments, affirmations, may occasionally be elegantly stated and delightful, but are more often awkward, and rarely offer the receiver any new insights. More important to acknowledge is that such feedback is rarely about the receiver. If I get inspired by a workshop, talk, or some other interaction my desire to praise is about meeting some need I have, and has little to do with the other. My positive feedback to you makes me feel good. Very few of us are willing to acknowledge this selfish aspect of positive feedback. When I get such feedback myself I try to be gracious, and accept it for exactly what it is: the other's need to be heard. This may be to genuinely express what is in their heart, or to connect, or perhaps to be thought well of. It has minimal impact on who I am or what I do.

So much for positive feedback. Now onto critical feedback. We've probably all been in situations where a well-meaning colleague or manager asks, "are you open to some feedback?". And then offers to go on a walk with us, or sit quietly somewhere. We all know what this means: we are about to be critiqued—and, worse still, by someone who assumes to be in a position to guide us to a better way of being. And then there's the whole peer review system, where we are asked to write "feedback" on our colleagues to their manager, often in secret. All feedback is destructive, but this particular brand is especially toxic.

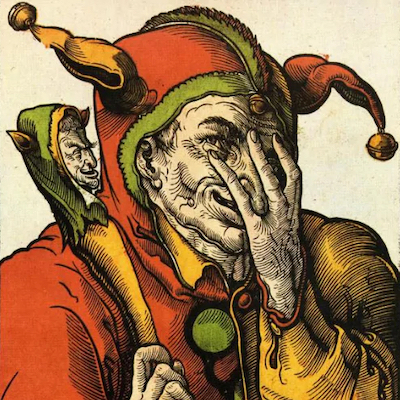

The arrogance of critical feedback must not be underestimated. It is deeply self-centered—and sheer folly—to believe we know how another should change, how they should improve. Every (uninvited) feedback conversation is a comedy of errors, a farce of misunderstanding, and fertile ground for resentment, mistrust, or even worse—fake trust.

Rather than getting caught in the destructive cycle of feedback, we need to explore other ways of learning through our interactions with others. One method my colleagues and I have experimented with is observation. Simple observation comes without judgement. Coupled with a quest to learn it becomes an enquiry rather than a platform for opinion. We have found this difficult, all of us trapped in our own opinions, with the corporate feedback model so ingrained in us. But we've been trying it, tripping up along the way, and learning through the process itself.

To give an example: I wanted to "give feedback" to a colleague that his making light of everything was an impediment (I believed) to his own learning—and frankly irritated me. I tried to phrase this as an observation: "You often use humour during our conversations."

For this to be authentic, and not a statement couched in my inherent prejudices I first needed to do some work. I needed to recognise that i) he wasn't doing this to annoy me, and ii) the trait may serve him in some way that I am unaware of. Freed of my opinions and my self-centredness, and open to possibilities I could make the observation with an air of enquiry.

Another team member said he observed it too. This opened up a dialog on the use of humour in difficult situations, how it can serve, how it can waylay, how it may affect others. This led to a conversation on safety and risk, on comfort and courage. The person still uses humour much as he did before. What changed is that he is more aware of the tendency, creating choice, and perhaps more importantly (for all in our team) I am no longer threatened by it, thus my responses to the humour are more accepting and I have implicit permission to confront it if I need to. Hard to capture all this in a short blog post, but I hope the idea comes across. If I had offered this as feedback it is likely I would have learned nothing, and my colleague would either feel he needed to stop a behaviour that was helpful to him, or he would have dismissed my feedback, entrenching both of us in our previously held opinions.

To summarise, feedback is judgment. It creates (or reinforces) an imbalanced power relationship between the giver and the receiver of the feedback. It may lead to resentment, entrenchment, and lack of trust. Feedback is manipulative, being almost completely focused on the one giving the feedback, with little concern for the one receiving it—except in as much as the receiver changes in the way the giver requires.

Observation gives us, whether in the position of offering or hearing the observation, an equal opportunity to learn. When learning is not two-way, there we have the root of an oppressive system.

Palo Alto, 24/05/2014 comment